One and half years ago, an idea was in the making—an idea that would reach hundreds of educators in Illinois, and innumerable amounts of students. Upon finishing an address as keynote speaker to a group of educators, Brian Fox Ellis was approached by a woman from the State Board of Education who was very interested in what he had to say about storytelling.

Ellis' theory is that storytelling is the most important tool a teacher can use to get students excited about language, and for teachers to teach literacy. The woman told him there were definite possibilities to incorporate storytelling with teaching adult literacy, and said he should give her a call. Ellis laughed as he thought of his initial reaction, "I never thought I'd hear from her again," he said.

Six months after the event, Ellis did indeed hear from the Board of Education. Lynn Plattner sent him an e-mail informing him there was a grant for a program dealing with teaching adult literacy through storytelling. When she called to tell him he received the grant for $100,000, Ellis was overjoyed. "This was a great opportunity with very few strings attached. The State Board of Education basically said, here's the money, you guys are the experts, so you tell us the best way to spend it."

The program began in a flurry of excitement—with promising results. Ellis and four other storytellers were chosen to head Arts in Education-Family Literacy. "The rate of adult functional literacy is appalling. By functional I mean the person can locate his name on a contract or read a street sign, not read the contract or use his skills to find a better job," Ellis said, explaining the importance of the program.

The storytellers come from many different areas in Illinois and each concentrates on a particular community college. According to Ellis, the committee decided to each come up with an individual project that when combined with the rest, would make a very complete kit for teaching and using storytelling in the classroom. Ellis said one storyteller, Dan Keding, took an oral history approach, while Mike Anderson concentrated on early childhood literacy workshops through Lincoln Land College.

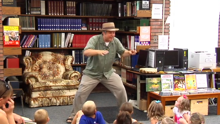

Ellis' method was three-pronged. Because children at risk for illiteracy come from families with illiterate adults, Ellis decided it was important to focus on early childhood literacy development with at-risk children. First, he worked with teachers from pre-schools such as Valeska Hinton, Head Start, Early Head Start, and others to reach the instructors about storytelling. He visited several classrooms to model the process and meet with the teachers to help them write lesson plans. The lesson plans, which will soon be posted on his web site, are all teacher-tested. "I said, 'You give me one lesson plan, and I'll give you 30.' The teachers really seemed to like that."

The second rung on the three-step ladder for Ellis was to encourage the instructors at Illinois Central College to teach storytelling. Ellis worked with instructors of GED, English as a Second Language, and ABE courses. Here, the focus was on family and childhood stories. "Everyone has a story to tell," Ellis said. "Everybody had a crazy uncle or a gossipy aunt, and people love to tell those stories."

Students and teachers learned storytelling and literacy through oral history and the collection of family histories. "This was quite rewarding. I even had some students send me poems and stories they wrote." Again, Ellis helped the adult literacy instructors develop lesson plans and formulate ideas using storytelling in their classes. The final step was to integrate the work of the early childhood and adult literacy teachers together, as well as have the groups meet to discuss.

One of Ellis' favorite parts of the program is what he calls Family Nights. Parents and children of each school Ellis visits come together one evening, and he speaks about storytelling. He gives the children questions to pose to their parents about family history, and the parents respond by virtually telling a story. "I love this part—everyone is laughing and talking, and a sort of well-ordered chaos breaks out. It's great,' he said. Ellis said storytelling is one of the finest art forms. "It is something inherently known by people even if they have little training."

This is what makes Family Nights so exciting. Parents "perform" for their children using voice inflection, body language, facial expressions, and illusion—all without even realizing it.

The first year of the program was so successful that the State Board of Education renewed the grant for $50,000. This year's program ends in May, Ellis said the focus is on Illinois valley Central College this year to extend into the rural communities. Another storyteller was also hired this year for a total of six. Though Ellis is not sure whether the grant will be renewed next year, he knows that even if it isn't the program will go on.

"I've impacted more than 100 teachers—the project will continue." Ellis said a five-year program would be ideal because it would cover most of Illinois. "Storytelling is a beautiful integration of literature and performance arts. Anyone can participate in folk art, and it exposes those who may not have the resources to the fine arts." Ellis said.

Upon completion of the program, the storytellers will have assembled a kit containing many necessary tools for combating adult illiteracy through storytelling for the community colleges. Ellis' lessons can be found at www.foxtalesint.com.